Designing Women For Magazine Covers Uncovered

Designing women for magazine covers as objects

“We Feature Women Like We Feature Cool Cars”

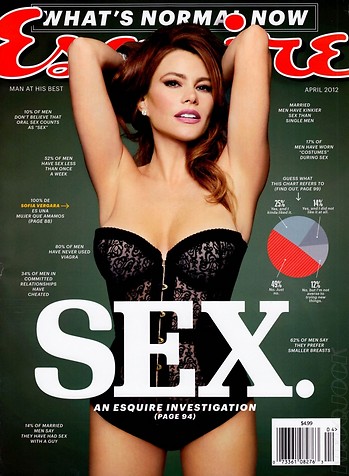

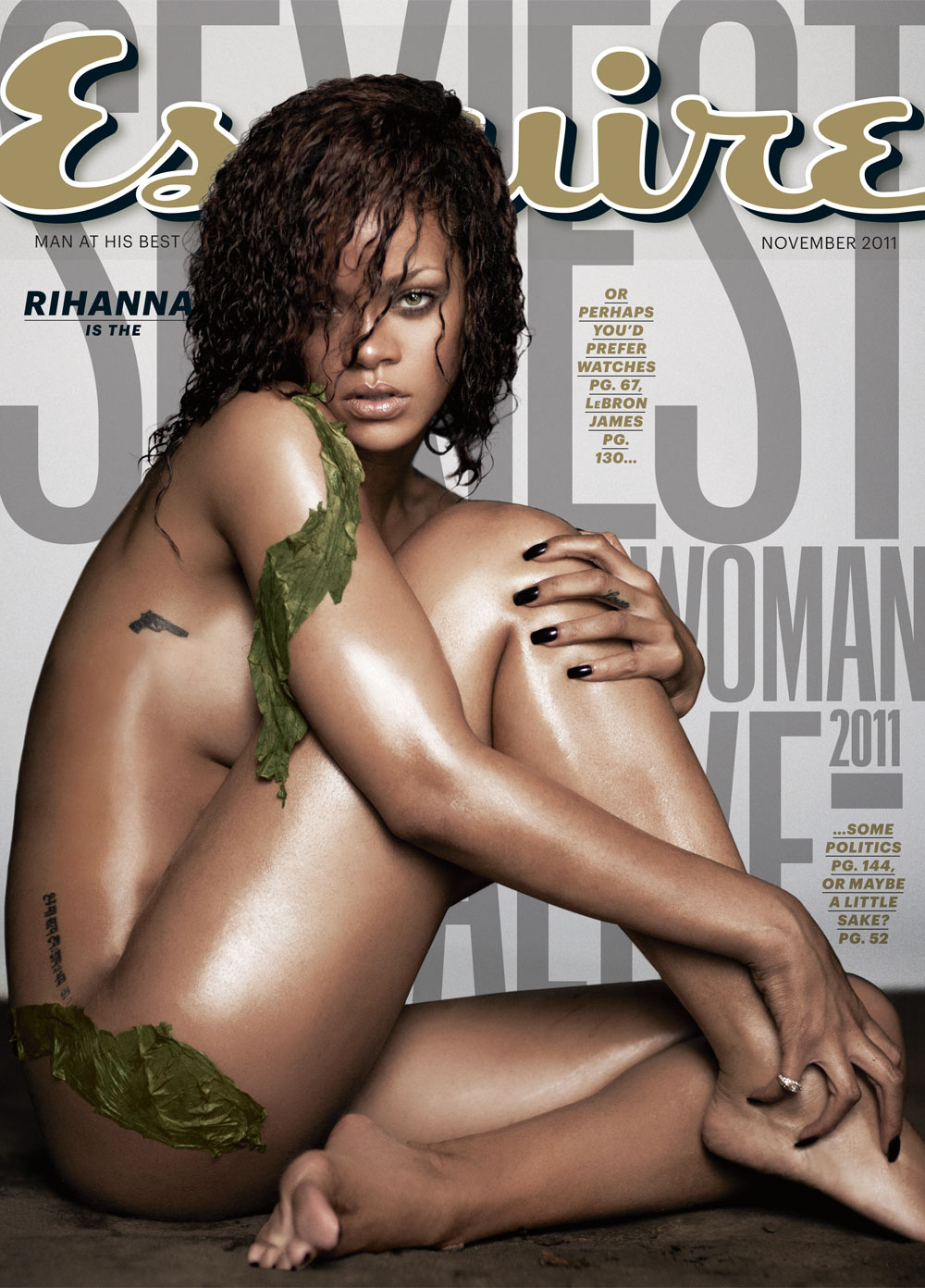

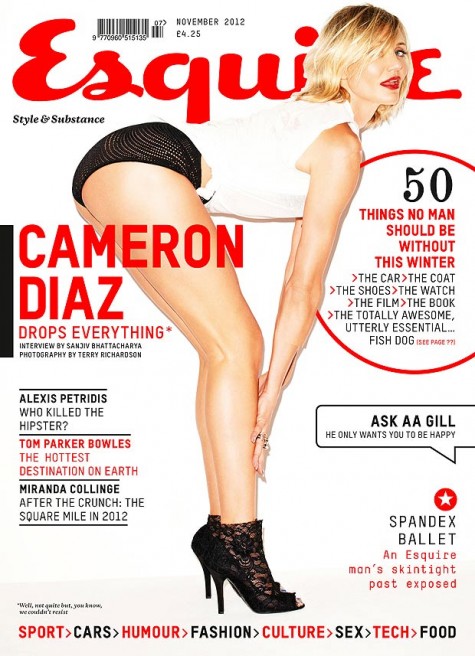

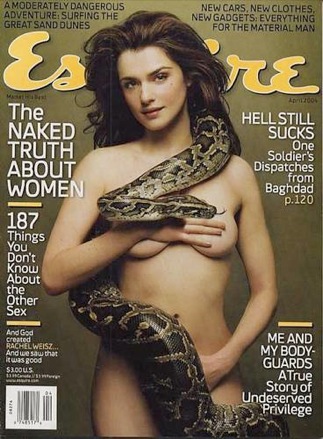

It’s no secret that images of women in the media are hypsersexualized, or to quote Oprah, “pornified,” but that didn’t stop the outrage this week when the editor of UK Esquire Alex Blimes told a conference “The women we feature in the magazine are ornamental,” he said. “They are objectified. I could lie to you and say we are interested in their brains as well. We are not.

Esquire provide pictures of girls in the same way we provide pictures of cool cars.” What?

He then dug himself in deeper by pointing out that they also feature “old” women on their covers – such as Cameron Diaz and Rachel Weisz.

“Not really old, but in their forties,” he clarified.

Twitter quickly named Blimes “Douche of the Day.” His comments sound like a clock turned back a century. But Blimes, for all his indefensible sliminess is right that men’s magazines adhere to the male gaze — and what’s more, so do women’s magazines.

Magazine covers are a lens into the way our culture thinks about gender, and the things we do —and don’t want to admit—about the place of women in the media and in our world. Let’s take a look.

Equal Opportunity Objectification? Nope.

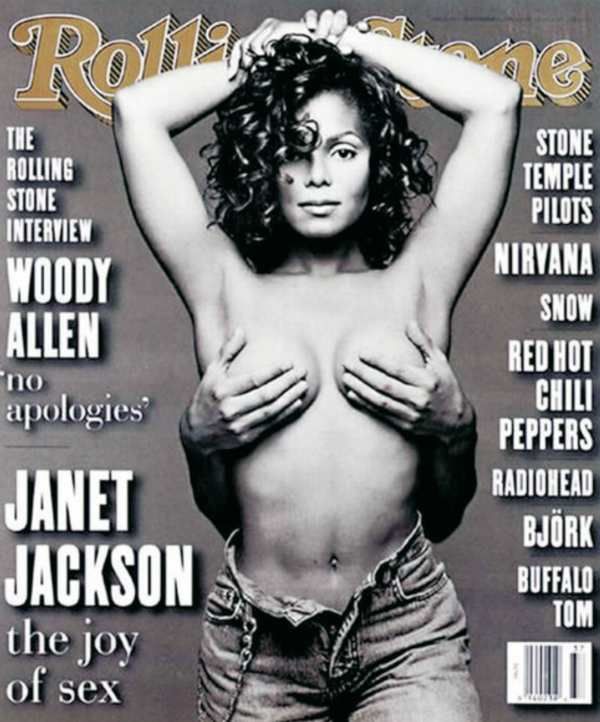

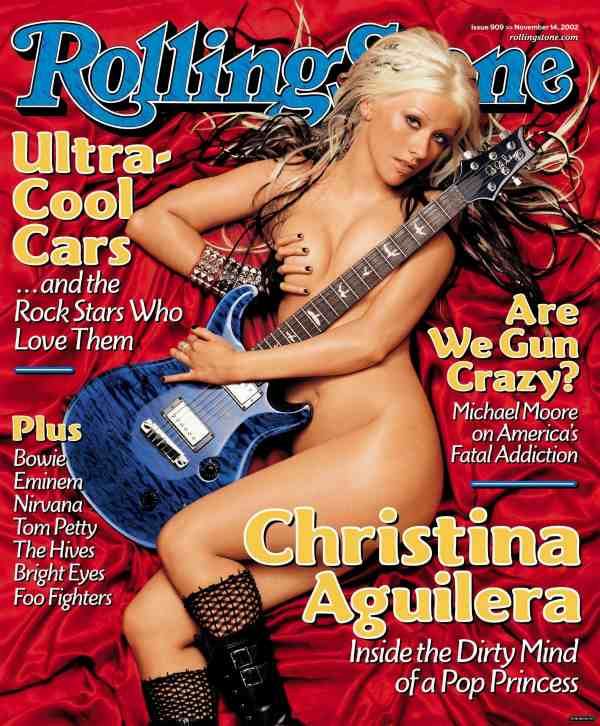

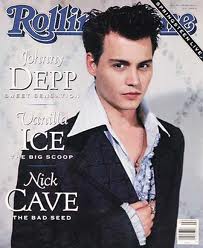

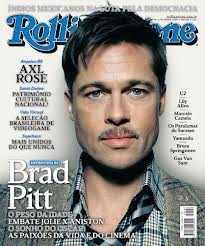

A study by the University of Buffalo called “Equal Opportunity Objectification? The Sexualization of Men and Women on the Cover of Rolling Stone” demonstrates that the portrayal of women in magazines has become increasingly sexualized over time.

The study analyzed more than 1,000 images from the covers of Rolling Stone from 1967 to 2009 to measure changes in the sexualization of both men and women in the magazine. “We chose Rolling Stone,” explains sociologist Hatton, “because it is a well-established pop culture media outlet. It is not explicitly about sex and relationships; foremost it is about music. But it also covers politics, film, television, and current events, and so offers a useful window into how women and men are portrayed generally in popular culture.”

They found that representations of both women and men have indeed become more sexualized over time.

Their most striking finding, however, was the change in how intensely sexualized images of women — but not men—have become.

In the 1960s they found that 11% of men and 44% of women on the covers of Rolling Stone were sexualized. In the 2000s, 17% of men were sexualized (an increase of 55% from the 1960s), and 83% of women were sexualized (an increase of 89%). “In the 2000s,” Hatton says, “there were 10 times more hypersexualized images of women than men, and 11 times more non-sexualized images of men than of women.”

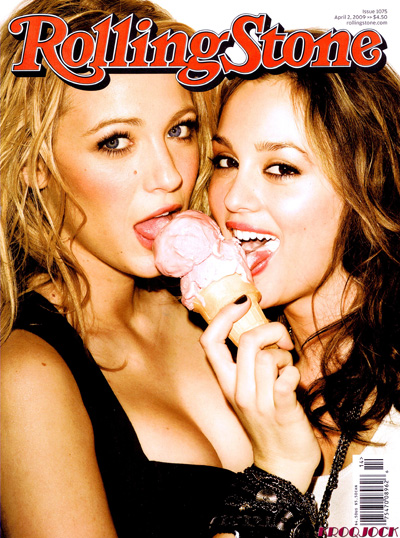

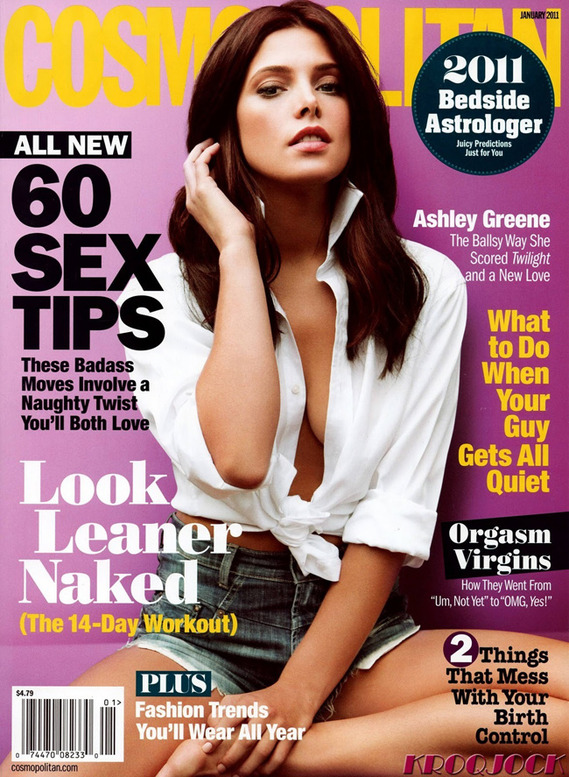

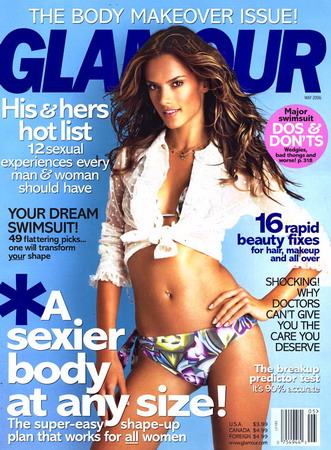

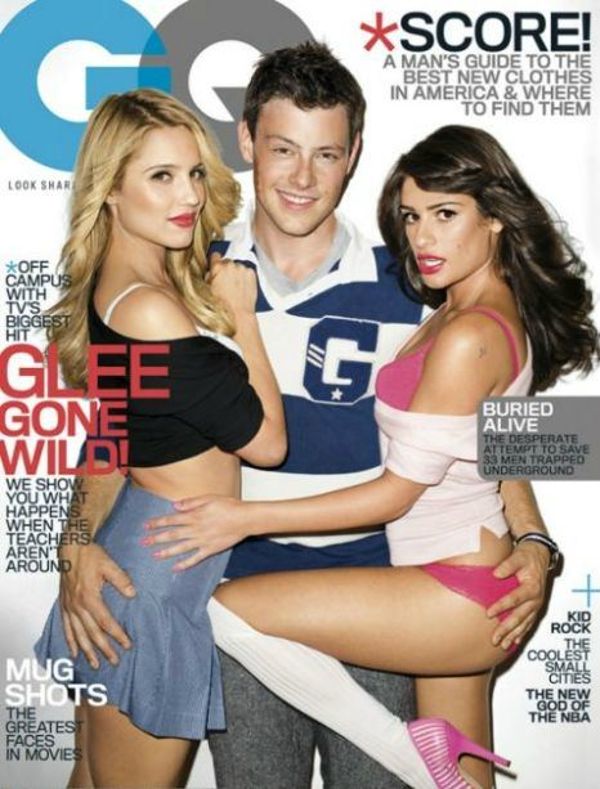

It’s Not Just Men’s Magazines

Curiously, men’s magazines and some women’s magazines often follow the same general formula. Men’s magazines are mostly based around eroticized images of women. And women’s magazines are based… around eroticized images of women. Why do GQ and Cosmopolitan often look like they’re selling the same things when, in theory, they’re selling them to different people?

Many of these magazines have been staffed and run by women for decades. Glamour has had a woman editor since its inception in 1939. If these magazines are produced by women, then why do they regularly signal the message that women and girls’ value lies in their youth, beauty and sexuality? Seventeen covers use headlines like “Flirty, Pretty, Cute and Amazing,” where the emphasis is above all else on looks. Women’s fashion magazines do break, however, from showing off the female body the same way men’s magazines do — instead, the beauty and attention is held in close-ups of the face.

Designing Women

Why? Women have made leaps and gains in the workplace and American culture since the 60s—shouldn’t our representation in magazines reflect this?

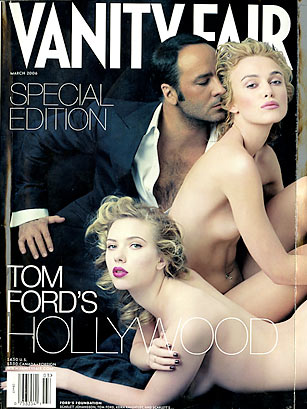

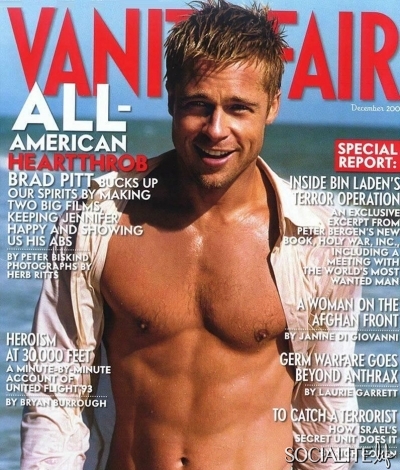

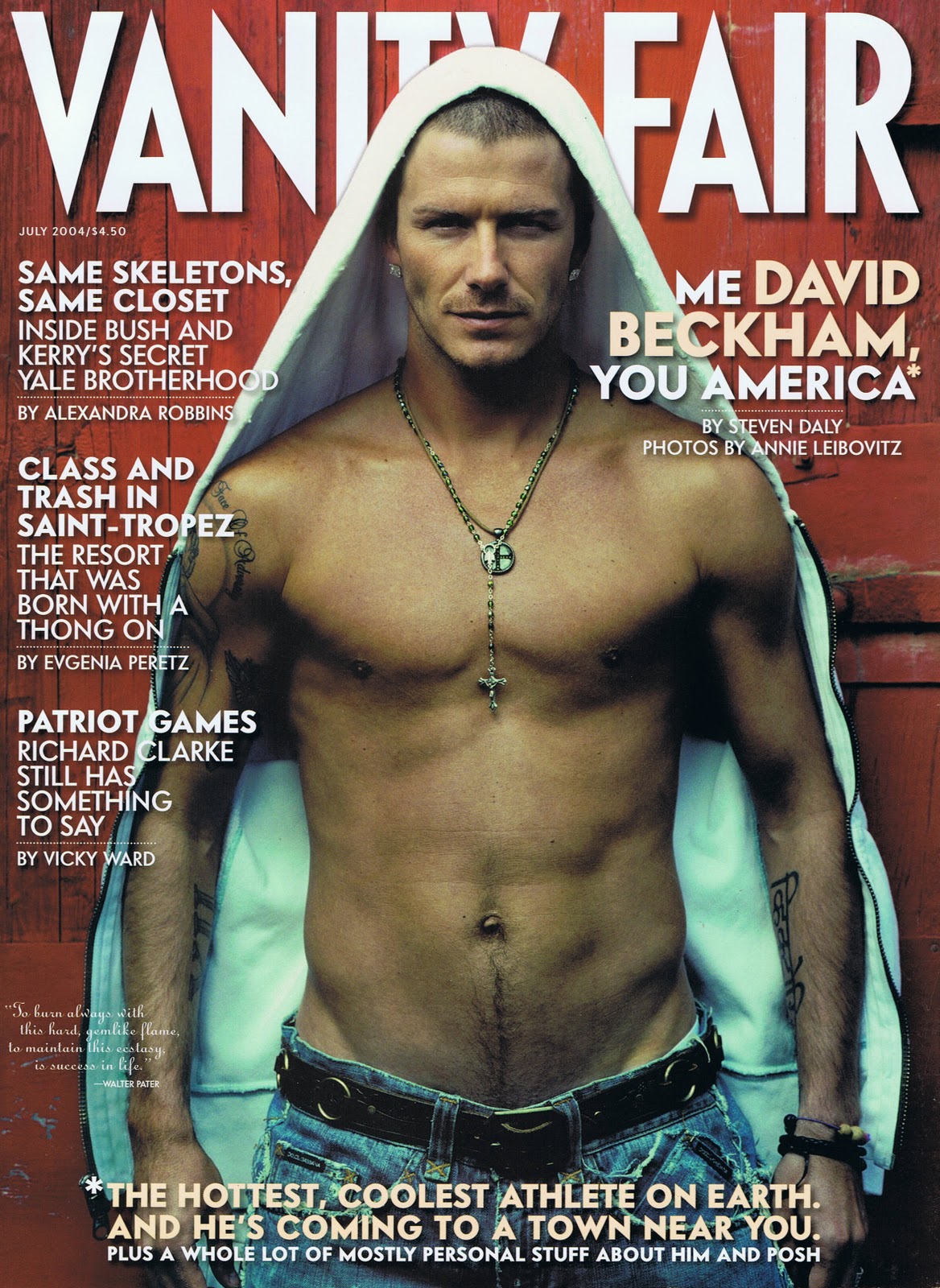

It may have to do with the way that our culture “designs” women. The Male Gaze describes the tendency of media to assume a male viewpoint even if it does not have a specific point of view, a long-standing trend in the advertising world as well. Buy the product, get the girl; for women, buy the product and get the guy. So women do not look—they are there to be looked at. When laying out these magazine covers, doesn’t it seem like it is intended for male appreciation, even though both men and women read, say, Vanity Fair?

This theory has a place in design, even when we don’t realize it. It’s what leads to a (usually male) director or cameraman’s focus on breasts, legs, butts, and other jiggly bits even when the piece isn’t meant to be intentionally raunchy. It has led to a Playboy-lite culture in our printed media. When attractive women are photographed, they are meant to look sexually primed and ready for consumption. When attractive men are photographed, they usually just appear cool and not sexual enough to threaten the (presumed) straight male audience.

For men, in lifestyle magazines, a ‘‘face-ism’’ bias exists, whereby men’s heads and faces are shown in greater detail than they are for women and seem less retouched. The corresponding bias for women is ‘‘body-ism,” where the focus is on women’s bodies or body parts (sometimes their heads are eliminated altogether).

Read the 12 questions your web designer should always ask you

What Design Tells Women

Many psychologists believe that women internalize the standards found in the media, leading to something called self-objectification. Self-objectifying individuals “come to view themselves as objects or ‘sights’ to be appreciated by others,” Harvard psychologist J.S. Aubrey says. “Design in media has a real psychological impact.”

Media exposure that is high in sexual objectification can socialize women to view our own bodies the same way that magazine editors treat women’s bodies on covers. We begin to see ourselves as objects for male desire, rather than considering our own desires. When we’re told again and again that the way women look is the thing that defines us, the uncomfortable truth is that a part of us may begin to believe it.

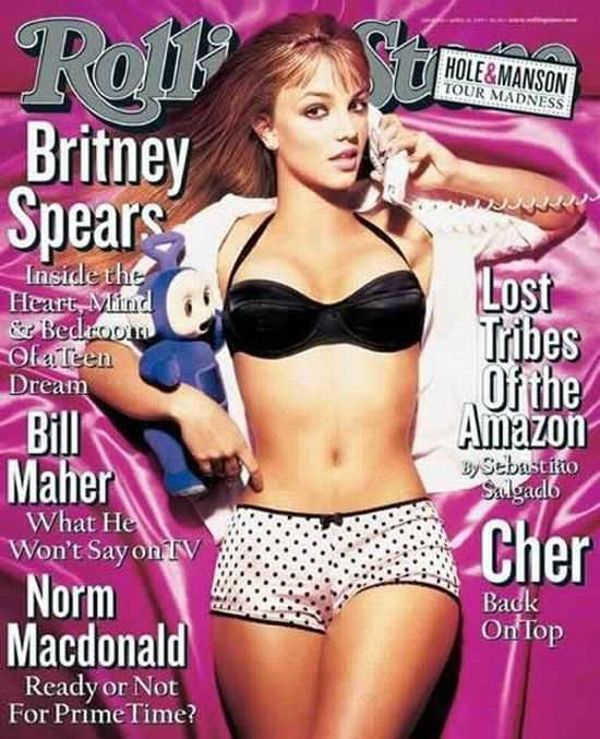

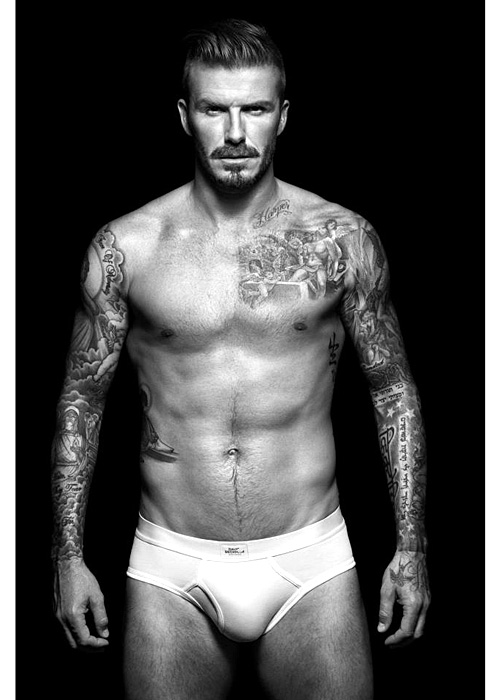

Just for fun…a healthy dose of male objectification

Is there a solution? Perhaps, bringing in more women behind the camera and in the board rooms of media outlets. And certainly calling out male editors like Alex Grimes when they defend the objectification of women. Changing the culture will be a long battle. But, if we have to surrender to viewing people as sex objects, and men get to have their fun with women on magazine covers, shouldn’t we? Let the Female Gaze begin.

Interestingly, it proved impossible for us to find a picture of a male celebrity in his underwear on the cover of a magazine that was not intended for a homosexual audience, even if there were more revealing shots in its pages. Finding a picture of a celebrity with no shirt on the cover was hard enough. So we guess women can bare all on the cover—who’d have thought men are the more demure sex?